Australian Cinema: What Cinema?

A theory I’ve heard raised a lot when talking about our national cinema is that we are constantly conflicted between American and European influences. This may be partly caused by a parallel crisis in identity on a much broader scale rooted in Australian constitution and culture. Born as a colony of the British Empire, but raised by the USA. Our cinema therefore exhibits a large disparity between art house, “intelligent” films of European sensibility and the more commercial genre films that hail from Hollywood.

I think our audiences are equally as confused and conflicted as a result. We are quick to judge and dismiss an Australian film when it is supposedly faux American – high concept, superficial ideas but ultimately ones that lack the sparkle without the might of $100 million budget behind it. On the other hand, when there is a sophisticated, distinctly Australian drama that makes use of a modest-sized budget and challenges the audience’s perspective of the world; the general public avoids them like the plague. The stigma is that contemporary Australian films are deliberately upsetting, depressing and boring stories about fringe communities in the outback. I may have exaggerated slightly, but speaking to friends, family and movie-goers that aren’t filmmakers – it is not far from the truth. To put it this way – Samson and Delilah would definitely not be everyone’s first choice for date night or after a long day at work (even though it is a good, powerful film).

This is a dilemma Australian producers face which can’t solely be blamed on the quality or nature of content…or money. How can we pander to an audience that is this cynical and hard to please?

Co-production is one way in which this problem is being tackled. More and more notable films over the last few years (most recently I, Frankenstein and The Great Gatsby) have been produced in conjunction with the US (or Europe) to achieve ideas and worlds belonging to high concept and/or genre films. The result is a film the majority of Australians would love to see at the cinema. Local talent and filmmakers get work in some capacity on these films, which is a plus too. This method of production is also guaranteed international exposure. Increasingly we see international film stars in home grown films (Ronan Keating in Goddess, or apparently Robert Pattinson in The Rover) to sweeten the appeal. I suspect there will be more and more of such productions in the future of Australian cinema.

A flip side to this supposed blanket solution is…through co-production and creating stories palatable to an international audience - do these films lose their sense of Australianness to them? If there is no Australian landscape, or accent or “Australian values” of mateship in the films, is it Australian anymore? And more importantly does it matter what effect that this has on the notion of our ‘national cinema’? Would Australian audiences even care? The majority probably won’t from the little research I’ve done and discovered; these films are quite successful commercially. Because of that, they will most likely enjoy increasing popularity.

But where does that leave us with films like Samson and Delilah, a bold perspective on contemporary Australian society? A film like this has little commercial value; doomed to circle independent and art house cinemas and never see a general release. I’m sure Warwick Thornton had not intended for the film to be a great mainstream success in the first place. But that defeats the purpose of a film doesn’t it? The message is clear: look at the lives of Indigenous Australians and see how their children are denied a chance to live fully because of the circumstances they are born into, this needs to change. This is a message for all of ‘white’ Australia (including our government and policy makers) and a plea to make those who are indifferent care. But the way the film presents this subject matter makes itself appealing only to a demographic of Australians who most likely are already aware, and not the people whose minds need changing.

Perhaps we need to change our thinking when it comes to films we write if we want our film industry to continue growing, there is a tendency towards social realist dramas that in its own honesty and earnest way of wanting audiences to connect, can often turn viewers away instead.

My intention is not to say that Australian filmmakers should just give up altogether and give audiences pure mindless escapism. But rather, combining the aforementioned two sides of Australian cinema – the intellectual and contemplative stories with strong plot-driven genre filmmaking – to find imaginative ways of imbuing relevant and real life context into films that the average viewer would want to watch. Because 99% of the time we watch films for the enjoyment of it, whether collectively as a social event or by ourselves, we’re after a certain amount of escapism from movies. Australia at the present does not do this well enough. I love watching a film and be lead to think and learn without being beaten over the head and preached to. For a fantastic example (forget the budget for the moment), District 9 shows how a film can address racial and political concerns in South Africa as well as open a discussion on the treatment of refugees within an imaginative context – an entertaining science fiction thriller. Other films like Black Swan, Snatch, Little Miss Sunshine, Juno, 28 Days Later (and almost every other Danny Boyle film ever made) all imaginative and intelligent films. With budgets that could've been made by us! Little Australia!

Another factor that deserves attention is the internet’s effect on traditional media and entertainment consumption, production and how we tell our stories now. Its ripple effect on the arts, media and technology is extensive and significant but we are only just seeing the beginning. It is also something that is hard to speak about if we are only referring to what is happening within Australia, as the internet surpasses national borders. At the lower end of the spectrum, the emergence of “pro-sumer” filmmaking, digital cinematography, crowd-funding and open film festivals such as Tropfest have given Australia’s young talent - and indeed worldwide - a platform to foster more diverse ideas and creativity (the good and the not-so-good). There are more indie films and smaller production houses producing content that rivals those of bigger production companies. Much like television, there is pressure to deliver higher quality content with smaller budgets.

There is also a rise of ‘On Demand’ films online. MIFF this year has begun offering online screenings for purchase. Vimeo has launched its first feature film, Some Girl(s) available exclusively online. As purists, we’d say that there’s no viewing experience better than one in a darkened cinema with a big screen, big sound. I agree. But the convenience of being able to avoid box office queues and watching a film when it best suits me is sadly just too tempting for me to stick to my pseudo-purist ideals.

This is something that the industry and filmmaking is forced to adapt to and acknowledge now, viewing trends are more user-dictated and not so much controlled by distribution companies and cinema chains. Independent filmmakers can bypass distribution gatekeepers and make their films accessible, and maybe even earn a buck or two. From a distribution point of view, online film festival screenings and on demand exclusive films fall under the “if you can’t beat them, join them” philosophy. This quite a new phenomenon and it remains to be seen whether it’s sustainable or profitable for both parties, keeping in mind that prices need to remain much lower than cinema rates to be competitive and a big enough incentive for a viewer to pay.

For films still fixed to a general or limited release in cinemas, marketing is all the more important for gaining enough exposure and convincing everyone to walk up to the box office. Which leads us to the need for more aggressive marketing. We can’t hold a candle to the amount of exposure Hollywood films receive here in Australia. Billboards, public transport, newspaper, television, online ads, etc. American distribution companies do well to saturate us with visual stimuli of their films. Where as our poor local films are nowhere to be seen because distribution companies no doubt are concerned with recuperating costs for small Australian features. However the less Australians hear about our films, the less likely they are to watch them at all. It then becomes a downward spiral.

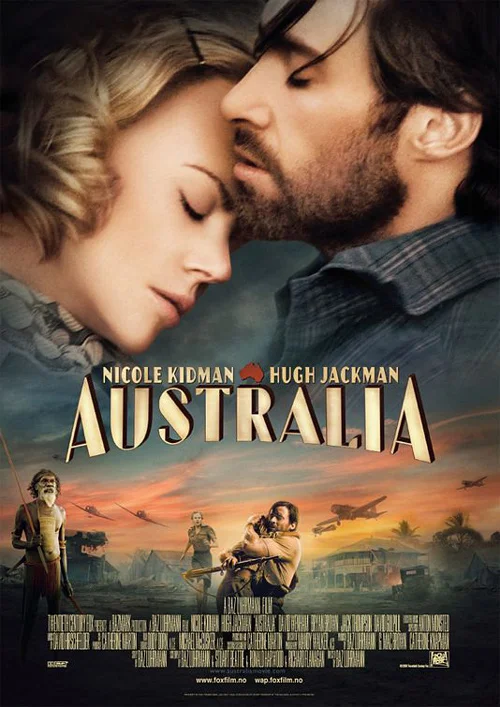

I think Baz Luhrmann’s most recent two films were successful at the box office locally partly because of the publicity it generated through its strategic marketing. Without going into discussing the quality of the film itself, Australia received much exposure from word-of-mouth as well as its partnership with Tourism Australia to promote the film as some sort of tourism campaign for the country.

Naturally there was backlash from cynical critics and the public reviewing Australia– with negative press about Luhrmann selling out and the film being over-hyped and underwhelming (which it was…sorry I couldn’t help it). But even that in itself was a form of publicity for the film. It garnered almost $50 million in takings at the box office locally, most likely many Australians went to see the film just so they could form their own opinions and be part of the conversation.

Australian advertising is certainly capable of innovative and grassroots campaigns for brands and products outside of the arts, what if we can find a way to invest the same attention into clever and inexpensive ways – particularly using strategic social media and online campaigns such as exclusive sneak peeks, transmedia narratives, etc. – to sell films as commercial product? Exposure for big films and small. What if we figured out some incentive to maintain a strong star system of Australian actors who have the power to pull in more of their fans to the cinema? Our film industry would stand a chance at being a competitive national cinema, and maybe finally tickle the fancy of our fussy local audience.